Tree Identification Walk in Kitsilano

Trip Report by Nina Shoroplova

On a pleasantly cool day, nineteen members of Nature Vancouver joined co-leader and photographer Caroline Penn and me to identify trees in Kitsilano Beach Park and over to Vancouver Maritime Museum. It was June 9, a day bookended by much hotter weather.

Our first tree was a hiba arborvitae, Thujopsis dolobrata, growing in the verge between Cornwall Avenue and a fence beside the Kitsilano Beach cycle path. It seems to be a rather nondescript coniferous evergreen until one looks closely at its many stems in the ground, accomplished by the tree’s layering its branches, and, of course, the superb pattern of its stomata on the underside of the needles. The leaves of most trees have gas-exchanging stomata on their undersurface; hiba’s stomata are eye-catching.

According to Stephen A. Spongberg’s A Reunion of Trees: The Discovery of Exotic Plants and Their Introduction into North American and European Landscapes, the first hiba arborvitae imported into Boston, US, came from Japan in 1861 as part of an assembly of exotics put together by George Rogers Hall, MD. The tree became part of the Arnold Arboretum in 1872 after James Arnold died in 1868, leaving part of his estate to the president and fellows of Harvard College. Since then, the single-species genus has spread across North America and elsewhere.

There are two immense Cedars of Lebanon, Cedrus libani, in this park. True cedars grow barrel-shaped upstanding cones that take two to three years to mature. These cones dissemble from high in the tree, one seed scale and two seeds at a time. The seeds separate from the seed scale in the air or on the ground—it is a long way down.

Plants of the World Online is housed at Kew Gardens, London (https://powo.science.kew.org/). It recognizes four species of true cedars: Cedrus atlantica, C. brevifolia, C. deodara, and C. libani. Other botanical authorities recognize only two species—C. deodara and C. libani—suggesting that C. deodara is one species and everything else is either C. libani or a variety of it. I leave it to the taxonomists to figure it out.

We tree identifiers took in the magnificence of both these Cedars of Lebanon: their height, their canopies, their branches hanging to the ground, their needle clusters, and the tree’s natural branch scars. Then someone found a fallen pollen cone and we discussed cedar’s reproductive cycle.

The pink bracts on a kousa dogwood, Cornus kousa, drew our eye. So did the shiny black leaves on a European beech, Fagus sylvatica; this year’s and last year’s fruit on a princess tree; and the catkins of female flowers turning into fruit on a Chinese wingnut, Pterocarya stenoptera.

As we stood beneath a row of three colossal Dutch elms, Ulmus × hollandica, we discussed Dutch elm disease, caused by a fungus, spread by a bark beetle, and devastating much of eastern North America. We were grateful that the disease has not made its presence a problem in British Columbia.

Under the umbrella of a London plane tree, Platanus × hispanica, I explained one of the ways I differentiate between the palmate leaves of a maple and those of a London plane: the palmate leaf of a maple has five veins; the palmate leaf of a London plane has three. Check it out.

Two species in Fabaceae, the pea, bean, and legume family, grow quite close to each other in this part: honeylocust, Gleditsia triacanthos, and black locust, Robinia pseudoacacia. Similar common names but quite different species. The honeylocust is quite young, thornless, and chartreuse in colour; perhaps it is the cultivar (cultivated variety) Gleditsia triacanthos ‘Sunburst’. Honeylocust’s flowers are catkins and its fruit are bean pods of seeds. The flowers of black locust on the other hand are racemes of fragrant white, botanically perfect flowers. They were almost over, but there were a few left on one of the four black locusts. The fruit of a black locust are again beans pods.

Having stopped at so many trees, we walked straight past a grove of unidentifiable elms, not very tall but with very dense foliage, and headed straight for the small wood that is framed on two sides by McNicoll Avenue and Maple Street, and on the other two side by the ocean. There we admired sweet chestnut, Castanea sativa, the edible chestnut. It is currently growing its male pollen catkins. Soon the female flowers will emerge to be subsequently pollinated by wind, beetles, bees, and flies.

On Maple Street near Ogden Avenue, we greatly admired a young dawn redwood, Metasequoia glyptostroboides, and its branchlets of opposite two-ranked needles. This is a species that once grew over many parts of Canada before the last big ice age cleared away trees, plants, soil, and rocks. Then dawn redwood was only found as a fossil until live specimens were discovered growing in the province of Sichuan in China. This young tree is another cultivar, given its golden needles; perhaps it is ‘Gold Rush’.

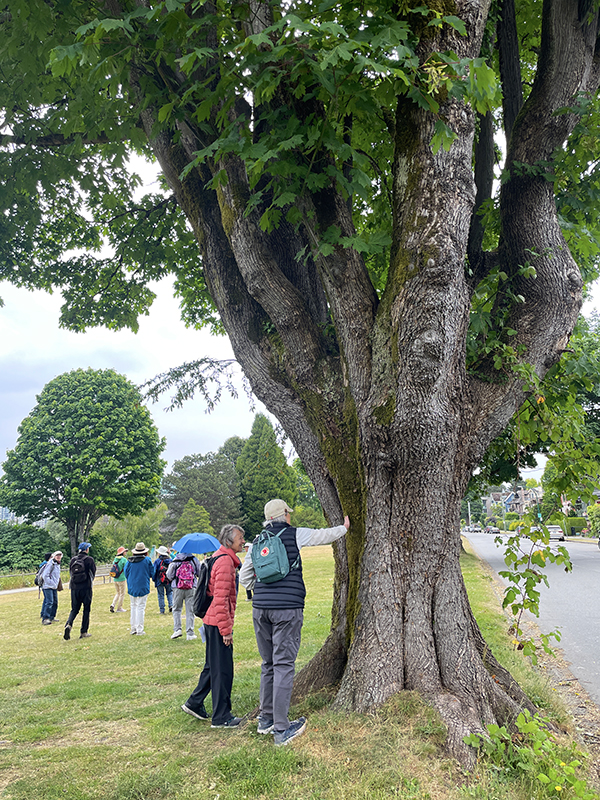

On the stretch of lawn en route to the Vancouver Maritime Museum, we looked at two maple species: a silver maple, Acer saccharinum, native in eastern Canada and the US, and a number of our native bigleaf maples, Acer macrophyllum.

And finally, we arrived at the last tree on this walk, a saw-leaf zelkova, Zelkova serrata, a tree in Ulmaceae, the elm family. A most enjoyable two-hour walk with a group of tree enthusiasts.